News

Alumni Testimonial: A career in the automotive industry

Philippe Ventre, class of 1954, has had an exceptional career in the automotive sector, and has agreed, on the occasion of the school's centenary, to look back on his career and his memories of ESTACA, from his dreams as a young student to his reflections as a former top executive:

"Born in 1934 into a family of teachers, I had a literary education which culminated in a baccalaureate in philosophy. Nothing foretold me of a career in industry, except an inexplicable passion for cars from an early age...

For a summer vacation in the early '50s, I found an "internship" with a garage owner who was willing to take on, free of charge, a young person who knew nothing about cars, but was willing. But instead of working as a mechanic, I spent my time as a co-driver for the boss, who had a passion for rallies and was preparing one aboard a DKW 3-cylinder 2-stroke, powerful and flexible, but consuming as much oil as petrol.

I refused to pursue a career in teaching, and since it was clearly impossible for me to take the competitive entrance exams for the grandes écoles, my parents agreed to let me take the competitive entrance exam for ETACA, which later became ESTACA.

Although I got off to a rocky start in mathematics, I was carried away by the wonder of all the other courses - mechanics, thermodynamics, strength of materials, auto - taught by working engineers who made them lively and concrete.

I was discovering the extent of the world that had fascinated me in my dreams, the knowledge I had to acquire in order to master my subject, and the sessions felt like a real pleasure.

I was discovering industrial drawing, the difficulties of using an inked line-drawing machine, and above all how to cleanly connect a compass arc with a straight line.

My worst memory: the design of a 3-threaded screw, the type used by Peugeot for its "hypoid" rear axles.

We had "projects" to carry out, with calculations, drawings and detailed, very Cartesian explanatory reports: starting hypotheses, methods used, conclusions, all to be presented in a typed file to be neat.

The biggest project was a 4-cylinder flat engine (Porche was already in vogue), but it seemed an aberration as soon as I realized the layout constraints it generated, especially with the advent of transverse engines.

Occasionally noting in one of the teachers an indication of areas to be explored, I supplemented the school courses, either at the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers, or at CLESIA, conferences organized by the SIA, Société des Ingénieurs de l'Automobile, to which I had obviously subscribed.

I left the school after a 7-month end-of-study internship at SIMCA, in Production Methods, which was not what I wanted to do, as I absolutely wanted to be in a Design Office, and the training I had received was just what I needed.

I joined the Régie Nationale des Usines Renault on June1, 1956.

After an initiation course, I joined the engine testing department, first at Billancourt, then in January 1957 at Rueil. My dream was beginning to take shape.

After the engine tests, I was asked to move on to testing all the chassis components, mainly suspension, and especially the drivetrains. This gave me a lot of contact with the road testers, and enriched my knowledge of everything to do with roadholding.

All my tests gave rise, as we had learned at school, to very detailed reports, typed up by the department secretary, and sent to the test applicants, copied to their bosses, and "for information" to the Director of Studies.

One day, one of my reports came back to me, crossed out and annotated with an angry "I don't need a lawyer". A little dismayed, and having spoken to my own supervisor, the Director of Studies came up to me in the middle of an essay, and said: "Your reports are good, but I don't have time to read all that literature, so why don't you write a one-page summary for the big bosses? Which is what I did for the rest of my career.

Nevertheless, he must have spotted me, because shortly afterwards he put me in charge of an entire "all tests" department, which meant I had to work on the R 16's shock absorbers, its aluminum engine - a first for the company - and its first automatic gearbox with hydraulic couplings.

This led me to consolidate my knowledge of the resistance of materials, (Woehler), and a kind of bible at the time "Timoshenko" and in that of vibrations with another bible that of "Den Hartog", the expert who had found and explained the reasons for the collapse of the famous "Tacoma Bridge".

I then moved on to the bodywork, mechanism, heating/air-conditioning and sealing equipment design office, during which time I took out around ten patents.

Then I was asked to create, and take responsibility for, a new sector designed to put a little science into the design of bodies in white, the "bodywork", whose torsion/bending behavior was totally unknown, the only literature being studies of square tubes with holes, to simulate a bus, American studies for school buses.

I discovered the need to know the English language well, and taught myself.

And when the major problems of protecting occupants in the event of an impact arose, it was only natural that, as the person in charge of structures, I should also become responsible for this area.

And my knowledge of English came in handy when I took part in numerous international conferences on these subjects, and for my dozens of publications on our work to improve body strength, and propose solutions for international regulatory testing; all in English.

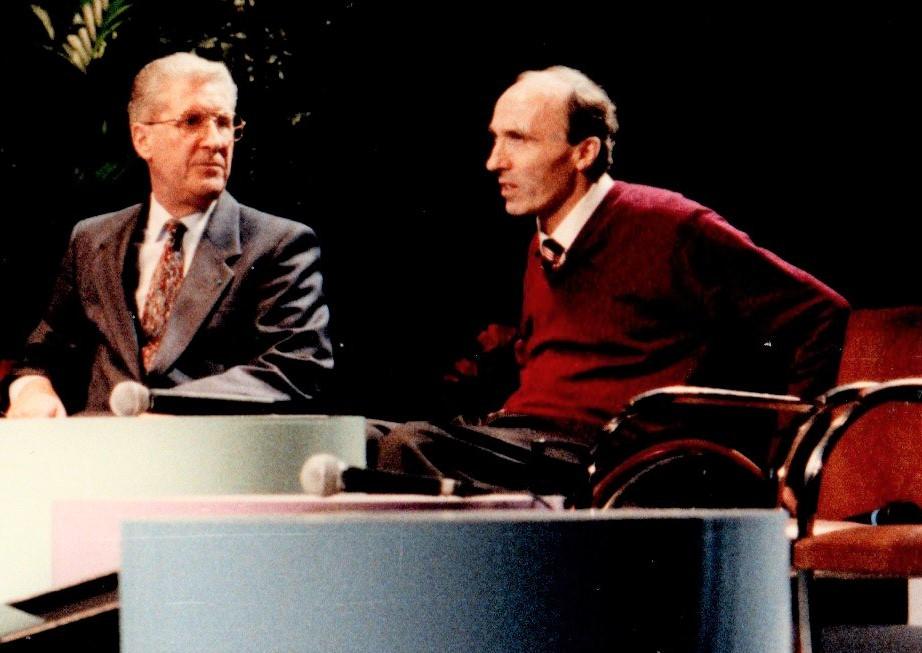

Philippe Ventre with Franck Williams, founder of Williams F1 Team

One in particular, arguing in favor of a homogeneous fleet of cars, rather than large, non-aggressive cars, and small cars reinforced for the current situation, caused a stir internationally and earned me an "award for engineering excellence" from the American National Hyway Traffic Administration.

And it was perhaps because of all these previous experiences that I was chosen, at the time of the Renault/American Motors deal, to be the first engineer to be sent, in February 1979, to Detroit, charged by the president at the time, Bernar Hanon, with setting up and directing an operation designed to put into production, a year after its release in France, an Americanized version of a vehicle still being studied at Rueil.

It was an extraordinary technical and human adventure, crowned by the success of the car, christened Alliance in the USA, which was named "Car of the Year" on its release.

Returning to France in December 1984, I took charge of Renault's Vehicle Design Office. I could never have imagined it.

After various organizational changes, and after having been responsible for all studies, including engines and transmissions, Chairman Louis Schweitzer decided on a major reorganization by merging the Design Office and Manufacturing Methods. As there could only be one driver at the wheel, I was appointed Vehicle Engineering Director for this new challenge. In this capacity, I became a member of the Renault Management Committee, the company's highest authority.

As an ESTACA graduate, I had under my command a host of great engineers, polytechniciens centraliens, guadzarts, Insa...; and all this without a hitch. Multiple, solid skills recognized by one's peers facilitate relationships.

School provided me with a solid foundation on which to build, stone by stone, a career that has gone far beyond my wildest dreams.

Given what she has given me, it seems only natural to support her today, and I appreciate all the work that the entire ESTACA Endowment Fund team, unknown but working towards the same goal, is doing for the good of the School.

And if all the Alumni, who are numerous after 100 years of existence, contributed more or less according to their income and needs, the School would have even more means to shine. The strength of a school is also its diaspora.

And after all this time, knowing that the concrete spirit of the school hasn't changed in substance, even if it has had to evolve as society has changed, I'm convinced that those who come out of it today (who may have, at times, the same little complex that I had at the start vis-à-vis the 3 grandes écoles) have all the weapons in hand to achieve great careers.

And all the more so as the world of transport faces "Himalayan" technological challenges!

Philippe Ventre, class of 1954

Some key dates in his career:

- 1954: Graduated from ETACA

-

1956 to 1970: RENAULT: Various positions in engine, chassis and body research and development

-

1970 to 1979: RENAULT: Head of Bodywork and Safety Department

- 1978: Award from the European Coil Coating Association in recognition of work on the development of pre-coated steel for corrosion protection.

- 1979: N.H.T.S.A. Safety Award for engineering excellence in occupant protection.

-

1979 to 1982 : RENAULT USA : Executive Vice President , General Manager Engineering and Planning Group

-

1982 to 1983: AMERICAN MOTORS: Vice President Quality and Product Integrity .

-

1983 to 1984: AMERICAN MOTORS: Vice President Product Engineering & Development

- 1983: Knight of the National Order of Merit

-

1985 to 1994: RENAULT: Director of Engineering and Vehicle Development

- 1991: Officer of the National Order of Merit.

-

1994 to 1998: RENAULT: Director of Engineering, Development and Vehicle Production Methods, member of the Renault Management Committee

-

1998 to 2002: FISITA: Vice-Chairman

- 1998: Knight of the Legion of Honor

-

2002 to 2004: FISITA: Chairman

-

2008 to 2020 : Mayor of Lacoste ( Hérault , France ) .

No comment

Log in to post comment. Log in.